A brief stop in the twilight zone

You stop by Whole Foods for $100 of groceries. On the way home, you glance at the receipt and see there’s been a terrible mistake - the total says not $100, but $1,000! You march back to the store and demand an explanation.

The manager assures you that the bill is correct: you’ve been charged ten times the stated prices, in order to subsidize the groceries of the other customers.

You look around at a sea of well heeled shoppers in business suits and Lululemon tights.

“This is ridiculous,” you protest, “I’m 25. I just moved here. Why am I buying groceries for these wealthy folks?”

The manager shrugs, and explains that it’s just how San Francisco works.

This all sounds like dystopian fantasy, but it’s a good analogy for SF’s housing market. Let me convince you with a specific example.

You could live well at 1133-44 Taylor Street

“1133”, a 10 unit structure built in 1908, is handsome inside and out. It’s perfectly situated atop Nob Hill, steps from Huntington Park and Grace Cathedral. According to its sales brochure:

The apartments feature hardwood floors, crown molding, vaulted ceilings, sky lights, recessed lighting, and in-unit washers & dryers.

1133 has one 1BR unit, six 2BRs and three 3 BRs. Market rents are about 20% more than the SF average.

Tenants have occupied the building for decades, moving in, enjoying the Nob Hill lifestyle, then naturally moving out when their circumstances changed.

That is, until 1979, when San Francisco’s rent control was enacted. After that date, leases ceased to be simple contracts for many and morphed into valuable financial assets, to be retained at any cost.

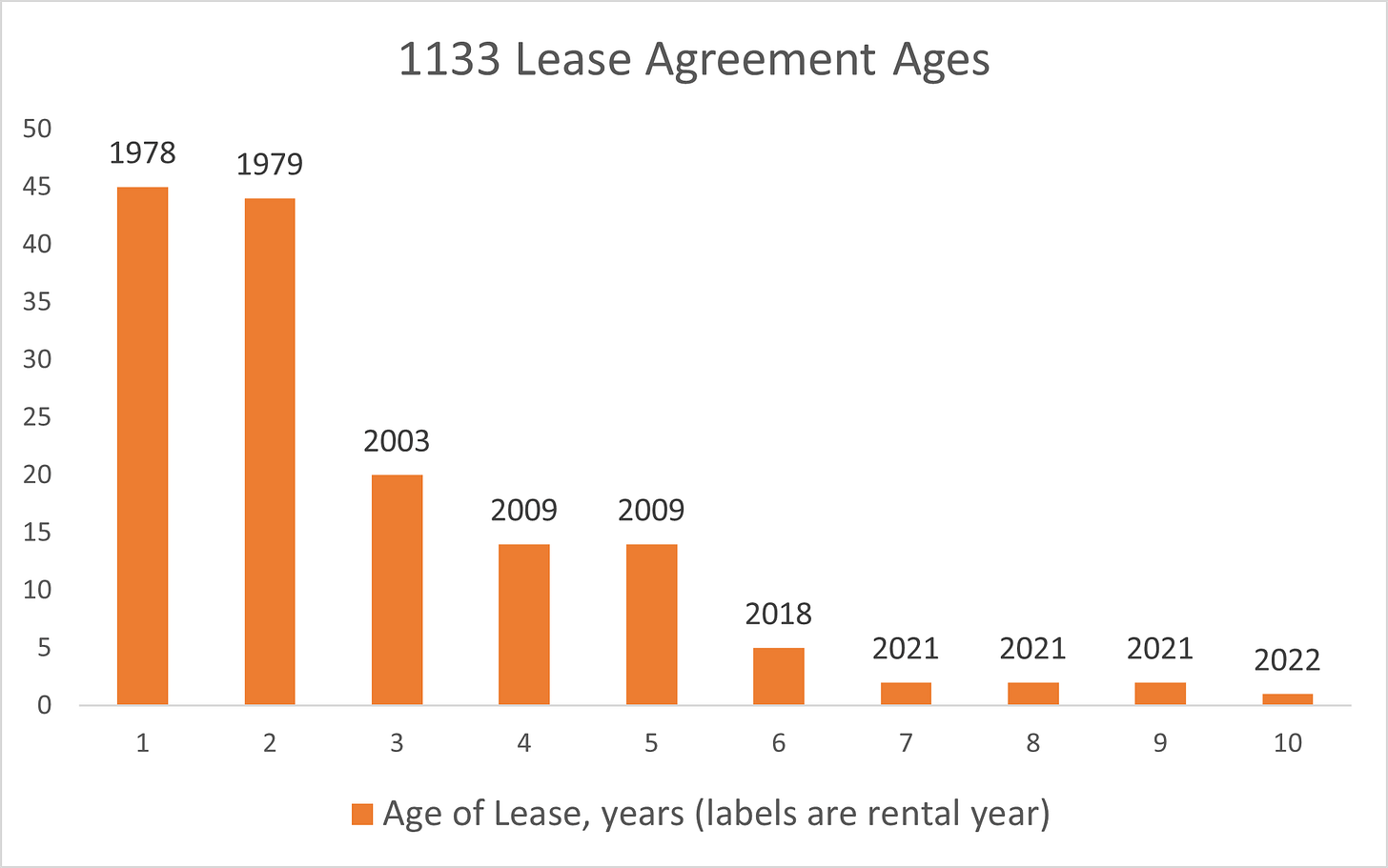

Here’s the year each rental agreement at 1133 was signed:

Half the leases are recent, probably reflecting the remote work changes of the covid era. But look at the other five - one is 45, another 44 years old!

These years aren’t random. They reflect unusual times when rents were briefly much lower than in future periods: 1978-79 due to inflation, 2003 due to the Dot-com bust, 2009 due to the Great Recession.

As a result, the rent per bedroom at 1133 varies from $385 per month to $3,750 per month - disparities as stark as any Twilight Zone Whole Foods. And it’s likely the folks paying the lowest rents are the richest residents. If they could afford top-of-Nob-Hill prices back in the 70s, they probably started with high paying careers. Imagine the wealth they’ve accumulated 45 years later, all while enjoying those low rents!

If rents were apportioned fairly, housing here would be quite affordable. In fact, SF would drop from the second most expensive rental market in the US to about the same as that of Scottsdale, AZ or Fort Lauderdale, FL, using the market vs actual rents from the 1133 sales brochure as a guide. Landlords could charge higher rents for long established tenants, allowing lower one for newer, poorer arrivals.

But, wouldn’t landlords just raise all rents? Competition would likely prevent this - even in the current situation, rents for newly vacant units here are falling, not rising.

Master Tenant Madness

It’s no surprise that the two longest leases at 1133 are for 3BR apartments - multi-bedroom flats are where rent control really downs a few shots of tequila, rips off its shirt, jumps on the bar and goes wild.

How? Well, while three names might be on an original lease, two could move out, and the third would become the “master tenant”, who is now the effective landlord of the unit, finding new tenants and collecting rent.

Master Tenant Madness was in the news last week, for a similar building three blocks away from 1133. Barbara Cohn had locked in a rent controlled lease in 1982, and since then had become real estate mogul, collecting rents for more than 70 subtenants over the years. The renter that, according to the story, finally drove Barbara out was “supposed to be temporary,” highlighting the Airbnb nature of these fiefdoms.

Legally, the master tenant is supposed charge proportional rents, but in practice that’s rarely case.

From a recent article on sfgate.com:

Search “master tenant” on Twitter and there are plenty of horror stories out there. A common grift? Master tenants charging subtenants an amount that adds up to more than the actual rent.

The story cites a typical example:

Michael was paying 75% of the total rent for one of three bedrooms in his apartment.

Worse, the master tenant may be long gone from SF, controlling his real estate empire from afar. Here’s a Quora question that could only have come from one city:

Even in cases where the original tenants remain in the unit, underpricing leads to overconsumption, exacerbating our housing shortage. Take the case of Ben and Cathi Wong, 40 year rent control beneficiaries. As the NBC article linked above notes:

They’ve lived in the same apartment for the past forty years, their two kids now grown and out of the house.

So the occupants of two of their three bedrooms are gone, leaving them vacant. In normal cities, the Wongs would downsize, saving them money and freeing space for new tenants. Here, the apartment sits mostly empty as the couple clings onto their sweetheart rental deal for dear life.

In another example, this article highlights one Richard Henegan, who is fighting eviction from his below market rate co-op. A quote from the article:

the 61-year-old chips away at packing up the three-bedroom apartment

One man, three bedrooms (city officials later stepped in to ensure he could keep living there, alone). Won’t see that in non-rent controlled cities.

While we’re on the subject of housing supply, recall from the famous Stanford study that rent control significantly reduced the number of rentals in SF, as many landlords wisely repurposed their units rather than face the revenue constraints of rent control.

At least rent control shouldn’t reduce the number of new apartments constructed, as it only applies to buildings built before 1979, right? Not if SF’s progressive city leadership has anything to say about it. They’re now demanding - illegally - rent control on new construction.

Back to 1133: There’s a fair chance that none of the occupants of those units with half-century old leases lived there when the original agreements were signed.

That’s because, unless a lease contains precisely the right wording, a non-original subtenant - one who moves in years or decades later - may actually become the new master tenant when the old one moves out. And God forbid the landlord loses the rental agreement, perhaps during a property sale - then no one knows anything, and the original tenant’s granddaughter could be in the unit for decades. I have friends (on the tenant end) in both of these situations.

Some say rent control keeps tenants from being “displaced” by large, unexpected rent increases. Maybe. But that also means a new person - one (debatably) adding more value to society, and who can thus pay more rent - can’t move in.

Remember Barbara, she of the 70 sub-tenants? She spent 40 years “as a local artist specializing in clay pots and stoneware”. While I’m sure her pots are nice, there may have been better uses for this unit, three blocks from the FiDi, during SF’s finance, legal, and tech booms over the past few decades.

SF’s extreme rent control also ages and area, as older people refuse to cede their spots in the jobs center to people in their working years. SF now has the oldest median age of any city in America. We’ve gone from the gold rush to the old rush.

Here’s the playground across the street from 1133. It’s mostly occupied by seniors these days:

Conclusion

The negatives of rent control - at least SF’s extreme version of it - far exceed any benefits.

Housing markets self-correct, never leading to the faux dystopias rent control advocates shout about on social media. “What happens where there are no more teachers or Starbucks employees in SF?”, they ask. The answer: Of the tens of thousands of cities in the world, how many can you name without teachers or cafe workers? If a place has no schools or cafes, it will no longer be desirable, and rents will drop. Also, a rising tide lifts all boats. If SF experiences a tech boom, for example, everyone’s salaries are likely to rise as money floods the city.

But, isn’t rent control just the renter’s equivalent of Prop 13, which limits how much property taxes can rise? While Prop 13 conceptually is just as bad as rent control, and should also be repealed, note a couple of differences: One, Prop 13 affects only one element of the cost of housing, unlike rent control, which covers 100% of it. Two, Prop 13 is easily circumvented (ask any SF property owner) by adding new “fees” to property tax bills, instead of percentage increases.

If you really are concerned about those teachers and baristas, you can protect them against large spikes in rent without SF’s extreme version of rent control, which limits increases to 2/3 the rate of inflation per year. At the state level, for example, California allows rents rise at a more reasonable 5% plus inflation per year. You can also means test rent control. There’s no reason a doctor making $400k/year should pay less rent than a teacher in an identical unit next door. That’s only fair in the eyes of SF progressives.

While we might want to provide subsidized housing for the poorest in society, most of SF’s residents are relatively wealthy, and not in need of inequitable market distortions that fuel the negative externalities above.

Thank you for common sense views about this insanity engulfing our city !

Agreed. I can think of 3 bankers with rent controlled apartments in sf. They leave it empty as pied a terre as the rent is so cheap.